After the demise of Ama-Nagavaloka Bappabhatti returned to Kanauj now ruled by former’s son Dunduka. Dunduka had already begun devoting himself to a dancing woman named Kantika and had made himself very obnoxious to his subjects and relations.

The history of India in the eighth century and the early decades of the ninth is shrouded in considerable mist. This much, however, is certain that in the first half of the eighth century the political scene of north India was dominated by the towering personalities of Yasovarman of Kanauj and Lalitaditya Muktapida of Kashmir. [1]

On the history of Yasovarman some authentic light is thrown by the Gaudavaho of Vakpati, his court poet, the Rajatarangini of Kalhana and the Chinese sources. They definitely prove that Yasovarman quit the north India scene some time in the middle of the century. But after his disappearance the history of Kanauj, the hub of eighth north Indian politics in this period, becomes extremely confused. [2]

However, some Jain works which deal with the life of Bappabhattisuri, the friend and preceptor of Ama Nagavaloka, the successor of Yasovarman, cast side lights on this dark period. Prominent among these works are the Prabandhakosa’[3] of Rajasekhara suri (1349), the Prabhavakacharita[4] of Prabhachandra suri (composed same time after Hemachandra, probably in the 14th century)[5] the Bappabhattisuricharita of Manikyasuri (13th or 14th century), [6] the Vividhatirthakalpa of Jinaprabhasuri (14th cent.), the Tapagachchhapattavali of Dharmasagaragani etc. [7]

Though these Jain works[8] are not contemporary records like the Gaudavaho, it is believed that the material preserved in them is based on continuous tradition and hence is quite reliable. But usually scholars have taken from such works isolated facts to support their this or that hypothesis. In order to avoid the pitfalls of such an approach, we propose to discuss all the facts of historical importance about Ama-Nagavaloka as they are known from the story of Bappabhatti and assess how far they are consonant with the material provided by other sources. [9]

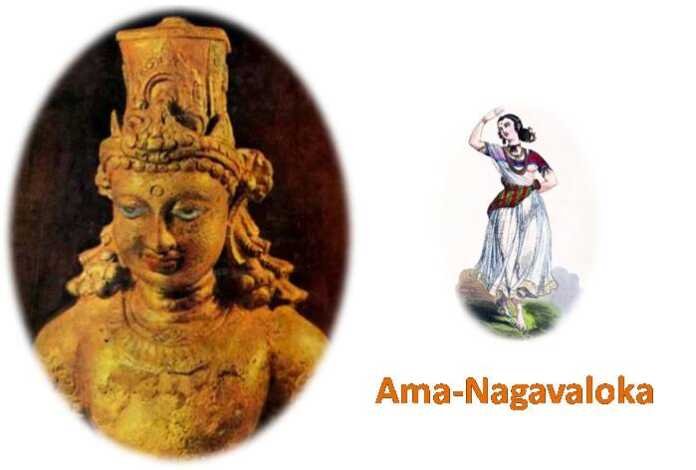

THE STORY OF BAPPABHATTI AND AMA-NAGAVALOKA

The various versions of the story of Bappabhatti as known from the above mentioned Jain sources agree on all the essential details. In the summary given below the differences of the various versions are mentioned in the footnotes. They, however, do not affect the central story much.

Bappabhatti was a disciple of Siddhasena of theGachchha of Modberakapura (Modhera, in Gujarat). He was born in the Vikrama year 800 (=743 A.D.) [10] and received his diksha as a Jain monk in V.E. 807 (=750 A.D.). In his childhood he became a friend of the prince Ama, the son of Yasovarman, the illustrious ruler of Kanauj,[11] who was the head-jewel of the famous dynasty of Chandragupta, by whom was made illustrious the already illustrious dynasty of the Mauryas.

Ama, who later on became famous as Nagavaloka (because of his taking hold of a poisonous cobra which succeeded in killing a mongoose in fight), was born of Yasodevi, during her temporary exile caused by the jealousy of a co-wife.

The friendship of Ama and Bappabhatti commenced when the prince, who was a spendthrift had been expelled by his father and was getting education at Modhera. When in course of time Yasovarman died and Ama succeeded to the throne the latter brought Bappabhatti from Modhera and received him with royal honours. This happened after 750 A.D., the date of the diksha of Bappabhatti and before 754 A.D., the year when he was raised to the dignity of a suri by his guru Siddhasena. [12]

After some time some misunderstanding arose between the two friends and Bappabhatti went to Lakshanavati (Lakhnauti), the capital of the king of Dharma of Gauda,[13] who was an enemy of Ama. Dharma gave shelter to Bappabhatti on the condition that the Jain monk would not return to Kanauj until the king Ama personally came to the Gauda court to invite his friend.

When Ama Nagavaloka heard of this condition he went to Lakshanavati in cognito and succeeded in extending a personal invitation to Bappabhatti without letting the king Dharma know of his identity. Thereupon Bappabhatti returned to Kanauj.

The story of Bappabhatti also has vakpatiraja the author of the Gaudavaha as one of its main characters. He has been described as “the head-jewel of the Kshatriyas and born of the Paramara clan.” Previously he was in Gauda enjoying the patronage of another ruler of the name Dharma (who ruled earlier than Dharma, the rival of Ama).

Vakpati was taken to Kanauj by Ama’s father Yasovarman [14] when the latter invaded Gauda and defeated and killed the elder Dharam. At Kanauj he composed the Gaudavadha and by this means got himself released from prison. Now, he came to Kanauj of his own accord to meet Bappabhatti and was, received as an honoured guest by Ama Nagavaloka.

On this occasion he composed two new works the Gaudabandha (distinct from the Gaudavaho) and the Mahumahavijaya. [15] After some time he felt dissatisfied with theconduct of Ama and retired to Mathura where, towards the end of his life, he was converted to Jainism by Bapppabhatti.

In the story of Bappabhatti a reference is also made to the conquest by Ama-Nagavaloka of Rajagiridurga ruled by Samudrasena, [16] though it was actually captured by him when in accordance with the prophecy of Bappabbatti, the sight of Bhoja, the infant grandson of the king, fell on it. Towards the end of his life Ama visited several tirthas including Stambhatirtha, Vimalagiri, Raivatagiri, Prabhasa and Magadhatirtha and ultimately gave up his life by immersing himself in the holy waters of the Ganga in the Vikrama year 890 (=833 A.D.) after duly accepting the Jain faith from Bappabhatti.

After the demise of Ama-Nagavaloka Bappabhatti returned to Kanauj now ruled by former’s son Dunduka. Dunduka had already begun devoting himself to a dancing woman named Kantika [17] and had made himself very obnoxious to his subjects and relations. He wanted to kill his son Bhoja because an astrologer had predicted that Bhoja would be a patricide.

Thereupon the queen of Dunduka and her brothers took Bhoja to Pataliputra. Now Dunduka directed the aged Bappabhatti to bring Bhoja back tothe capital. Not wishing to follow the king’s command, Bappabbatti gave up his life in the Vikrama year 895 (=838 A.D.) af the age of 95. The prince Bhoja was extremely moved by the sad demise of the Jain saint. He returned to Kanauj, killed his father and occupied the throne. [18]

AUTHENTICITY OF THE STORY

This is the history of Ama-Nagavaloka known from the life-story of Bappabhattisuri. We have divested it of all the miraculous elements and unnecessary datails which were intended to glorify the Jain faith and the achievements of Bappabhatti. But even in the historical part of the story there are several facts which are of doubtful nature. There are also several obvious inaccurate statements in some versions of the story. However, most of them may be easily explained or are of no consequence.

For example the Prabandhakosa gives the credit of killing Dharma, the king of Gauda and of patronising Vakpati to Yasodharman whose known date is 532 A.D. But this inaccuracy may be dismissed, as a copyists’ error for in the Devanagari characters the letters dha and va are so similar as easily to lead to a confusion of one for the other. Similarly, the fact that Rajasekhara suri has placed Lakshanavati in Deccan is of no consequence for he places Gauda desa also in that direction.

The Jain authors also make Vakpati write the Mahumahavijaya after he had already composed the Gaudavaho while Vakpati himself has referred to that work in his Gaudavaho. [19] But this point merely proves that the literary chronology of the Jain author was at fault; it does not go against the admissibility of their testimony.

Another line of attack on the authenticity of the Jain tradition is concerned with the personality and achievements of Bappabhatti. It is claimed that he was given diksha as a recluse at the age of seven, was raised to the dignity of a suri at the age of eleven and became a chosen Ama even before that.

He is also credited with converting preceptor of Vakpati, Ama and many others to the Jain faith. But if we remember that the story was basically intended to glorify the Jain faith and also keep in mind the life of Sankracharya who became a master of all the sastras in his childhood, such scepticism in the Jain story would loose much of its force.

REVIEW OF THEORIES REGARDING AMA-NAGAVALOKA

As regards the historical data concerning the king Ama-Nagavaloka himself, the most doubtful point of the Jain sources is that they ascribe him an abnormally long life of more thanhundred years and what is more a long reign of 83 years. Before he began his education at Modherakapura with Bappabhatti in c.750 A.D. he had been expelled by his father Yasovarman on account of his being a spendthrift and had become addicted to youthful follies.

Therefore he must have been more than eighteen years old in 750 A.D. and thus at the time of his death in 833 he could not have been less than hundred years old.

Such a long life is not impossible but when the Jain works assert that out of these hundred years he ruled for at least 83 years, i. e. from c.750 A.D. to 833, the thing becomes extremely doubtful. On the face of it, it appears palpably impossible that a king could rule for 83 years in that age of kaleidoscopic changes.

It becomes still more difficult to believe in veiw of the fact that our sources reveal that at least three Ayudha kings namely Vajrayudha, Indrayudha and Chakrayudha ruled over kanauj in the period when Ama-Nagavaloka is said to have been on the throne.[20]

In order to solve this difficulty many scholars such as G. H. Ojha, R.C. Majumdar, R.S. Tripathi and And Dasaratha Sharma identify Ama-Nagavaloka with Nagabhata II of the Gurjara Pratihara dynasty.[21]

But they find it impossible to explain the fact that Ama-Nagavaloka was the son of Yasovarman who died in c 750 while Nagabhata II was the son of Vatsaraja who was ruling in 783 A.D.[22]

They are, therefore, constrained to assume that the details of the life story of Bappabhatti are “mixed indeed with plenty of fiction.[23]

On the other hand many scholars accept Ama-Nagavaloka as the son and successor of Yasovarman without bothering to take into consideration the fact that Ama is said to have died in 833 A.D.[24]

A third group of scholars including S.K. Aiyangar and G.C. Choudhary believe that Ama-Nagavaloka, the son of Yasovarman indeed ruled at Kanauj from c.750 to 833 A.D. and was followed in turn by Dunduka and Bhoja and suggest that in that period the Gurjara Pratiharas ruled somewhere else.[25]

But, such a view not only implies a belief in an abnormally long reign of 83 years of Ama-Nagavaloka, but also invites insurmountable difficulties in the reconstruction of the history of tripartite struggle in this period and makes it impossible to explain. the rule of Vajrayudha, Indrayudha and Chakrayudha at Kanauj in the age of Nagabhata II and Dharmapala.

Thus none of the above mentioned theories solves the riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka satisfactorily. As a reaction to this confusion scholars such as B.P. Sinha have maintained that it is “difficult to base any conclusion on such works of very doubtful value.”. [26]

But this drastic verdict against the authenticity of these Jain works is not at all necessary, for even if they fall short of historical compositions in many ways. it would still be demanding too much to dismiss them as completely worthless.

The Jain literature is famous for its historical value. The works under discussion refer to such historical personages as Yasovarman, Nagavaloka, Vakpati and Dharma (pala). They claim that they are based on the tradition handed down by the learned men. They, therefore, cannot and should not be discarded as entirely valueless.

COMPOSITE PERSONALITY OF AMA-NAGAVALOKA

To us it appears that the story of Bappabhatti and Nagavaloka would become intelligible if it is presumed that its authors have confused the personalities of the two kings of the name of Nagavaloka who flourished at two different times, though they may (or may not) be correct in assigning a long life to Bappabhatti himself.

The first Nagavaloka was cbviously the son of Yasovarman as the tradition asserts. There is nothing in the facts known from other sources to doubt this assertion. The date of Yasovarman as indicated by this tradition (after Vikrama year 807=750 AD when Ama was only a prince but before V.E. 811=754 A.D. when he the Chinese annals. [27]

It proves that the was already ruling) is generally supported by Kalhana’s Rajatarangini and authors of the life story ofBappabhatti had reliable data for this aspect of their testimony. This conclusion becomes irresistible by the fact that they refer to Vakpati, the author of the Gaudavaho as a contemporary of Yasovarman and his son.

Here it is interesting to note that theexistence of a king namedAma who ruled overKanauj is also known to the Dharmaranya Section of the BrahinaKhanda of the Skanda Purana.[28]

Though the whole account of the passage in question is woven upon the mythical in a complicated manner and it is almost impossible to interpret its details in a rational manner, it is quite obvious that it is referring to the king Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain tradition.

It mentions him ruler of Kanauj (Kanyakubjadhipatih) and refers to his sarvabhaumatva or paramountcy. It also tells us that his daughter Ratnaganga was converted to the Jain faith by a Jivika (Ajivika i e. Jain monk) Indrasuri.

Ama himself was devoted to the righteous Dharma (Satyadharma parayana) but later on he also embraced Jainism. These facts indicate that the existence of a ruler of Kanauj named Ama was also known to the author of the Skanda Purana.

Thus the existence of a king name Ama alias Nagavaloka in the post Yasovarman period appears to have been a fact. But all the facts recorded by the Jain authors about Ama-Nagavaloka are not applicable to this ruler; many of them are obviously applicable to Nagabhata II the son of Vatsaraja Pratihara. Firstly, Nagavaloka died in 833 A D. Thus he belonged to the period of Nagabhata II, for the known date of Nagabhata II from inscriptions is V.E. 872 (=815 A.D.). [29]

Secondly, Nagavaloka was succeeded by his son Dunduka who ruled for only a short time and was succeeded by Bhoja, the grandson of Nagavaloka. Similarly Nagabbata II was succeeded by his son Ramabhadra who after a short while was followed by Bhoja, the grandson of Nagabhata II. Thus, but for the difference in the names of the sons of Nagabhata II and Nagavaloka, the two traditions perfectly agree.

Thirdly the Gurjar Pratiharas ruled over Kanauj at least from the closing years of the reign of Nagabhata II, [30] while Nagavaloka is described as a ruler of Kanyakubja. The hostility of Dharmapala with Nagabhata II is also a historical fact and in the Jain tradition the king Dharma is said to have been on hostile terms with Nagavaloka.

The conclusive evidence for the identity of Nagavaloka with Nagabhata II is provided by a reference to the conquest of Rajagiridurga by Nagavaloka in the Jain tradition, a feat which has been explicitly attributed to Nagabhata II in the verse 11 of the Gwalior Prasasti [31] of Minira Bhoja.[32]

CAUSE OF THE CONFUSION

Thus it is obvious that the Nagavaloka of the Jain story is a composite personality in which certain facts about Nagabhata II Pratihara, the son of the son of Vatsaraja have been ascribed to Ama-Nagavaloka, the Yasovarman. The cause of this confusion is quite obvious. Ama, the son of Yasovarman became famous as Nagavaloka while Nagabhata II was also known by this Viruda. [33]

This is conclusively proved by the Pathari inscription of Parabala dated V E. 917 (=861 A.D. 29) according to which Parabala’s father Karkaraja invaded the territories of Nagavaloka and defeated him in a bloody fight.Now, this Nagavaloka who flourishedonly a generation earlier than 861 A.D. was obviously Nagabhata II; he could not have been the son of Yasovarman who died in c. 750 A.D.[34]

That Nagabhata II was known as Nagavaloka is also proved by the Harsha stone inscription of Vigraharaja Chahamana, dated V.E. 1030 (=973 A.D.) where one of his predecessors Guvaka I is described as having obtained honour at the court of Nagavaloka.[35]

As Guvaka I flourished in the first half of ninth century, his patron Nagavaloka can only be identified with Nagabhata II Thus we find that in the age to which the life of Bappabhatti has been ascribed by the Jains (743-838 A.D.), two kings became famous as Nagavaloka.

Further, both of them ruled over Kanauj. It is also possible, if only remotely, that both of them patronized the Jain saint. It was, therefore, quite natural for the authors of the life of Bappabhatti, who composed their works in the thirteenth century or after, to identify these two rulers. But once the contradictions involved in their supposition are clearly understood and the cause of this confusion is appreciated, it becomes easy to separate the two streams of traditions which have got mixed up in their works.

SUGGESTION

This suggestion is important from several points of view. Firstly, it clears a lot of confusion regarding the history of north India in the second half of the eighth and early decades of the ninth century. It means that Ama-Nagavaloka, who ascended the throne in c. 750 did not rule till 833 A.D. and that Dunduka and Bhoja were not his successors; they were the successors of Nagabhata II who died in 833 A.D.

Thus, without rejecting the historicity of Ama-Nagavaloka, the son of Yasovarman, we obtain a gap in the history of Kanauj between Ama-Nagavaloka and Nagabhata II in which the three Ayudha kings- Vajrayudha, Indrayudha and Chakrayudha may easily be placed.

It obviates the necessity of declaring the Ayudha rule over Kanauj as a concoction or identifying Indrayudha of inscriptions and literature with Ama-Nagavaloka as S. K. Aiyangar and G.C. Choudhary have done.

G.C. Choudhary has become so much confused by the untenability of his supposition that he has identified Vajrayudha[36] and Indrayudha[37] both with Ama-Nagavaloka. Our suggestion also makes it easier to reconstruct the history of the Rashtrakuta invasions on north India in this period, for now it remains no longer necessary to start with the assumption that Ama-Nagavaloka, the son of Yasovarman ruled over Kanauj from c. 750 to 833 A.D.

Secondly, our suggestion throws a new light on the history of Ramabhadra, the son of Nagabhata II. For now he can be confidently identified with Dunduka of the Jain Tradition. It was suspected by R.C. Majumdar long ago that Ramabhadra was a very weak monarch. [38] But unfortunately be relied on the rather weak evidence of the Barah Copper plate [39] and the Daulatpura inscription [40] from which it appears that two grants one in the Kalanjaramandala and the other in the Gurjaratrabhumi fell into abeyance during Ramabhadra’s reign. It indicates that his reign was a period of stress and strain.

And Dasaratha Sharma questioned the inference of Majumdar, [41] but the Gwalior prasasti of Bhoja (Verse 12) also explicitly refers to “the cruel and haughtly commanders” whom Ramabhadra had subdued with the help of his subordinate kings. These haughty commanders were identified by Majumdar and Tripathi with the Palas.

But to us it appears that the author of the prasasti could not have mentioned the Pala enemies of the Pratiharas as cruel and haughty commanders, they must have been the rebellious generals of Ramabhadra himself.

But why did the Pratihara generals raise the banner of revolt against Ramabhadra? Perhaps the answer is provided by the story of Bappabhatti according to which Dunduka, identified with Ramabhadra, had become infatuated with a dancing girl named Kantika and had made himself obnoxious to his people and relations.

Majumdar, Tripathi and Dasaratha Sharma could not utilize the material of the Jain tradition for the reconstructions of the history of Ramabhadra because they were confused by the fact that in the tradition Dunduka has been made the grandson of Yasovarman.

But if this tradition is interpreted in the light of our suggestion the whole thing becomes transparent and the evidence of the Gwalior prasasti for the reign of Ramabhadra and the Jain testimony for the reign of Dunduka become complementary to each other.

[1] S. R. Goyal, The Riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain Tradition, Proceedings of Rajasthan History Congress, 1976, pp. 26-36.

[2] S. R. Goyal, The Riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain Tradition, Proceedings of Rajasthan History Congress, 1976, pp. 26-36.

[3] The account of the life of Bappabhatti is given in its Bappabhattisuri prabandha.

[4] The story of Bappabhatti as given in this work is merely a versified amplification of that which is given by Rajasekhara.

[5] In addition to writing a story of Hemachandra’s life, Prabhachandra speaks of him as having written ‘long ago’ (pura).

[6] This date is conjectural, there being no ground for it beyond the belief that works of this kind were written in this period.

[7] The Vicharasaraprakarana of Pradyumnasuri (13th cent.), the Gathasahasri of Samayasundara and a Pattavali by Ravivardhana also contain some information on the life of Bappabhatti.

[8] For all these works, except the Tapagachchhapattavali, vide Gaudavaho ed. by S.P. Pandit, Intro. pp. cxxv-clxi where all the relevant material from them has been reproduced.

[9] S. R. Goyal, The Riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain Tradition, Proceedings of Rajasthan History Congress, 1976, pp. 26-36.

[10] According to the Vividhatirthakalpa, the Gatha ahasri and the Vicharasaraprakarana Bappabhatti was born after Vikrama year 830 (=774 A.D.).

[11] In the Bappabhattisuricharita Yasovarman is described as the king of Kanyakubja who ruled at Gopagiri or Gwalior. The Prabandhakosa also locates his capital at Gopalagiridurga (Gwalior)

[12] S. R. Goyal, The Riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain Tradition, Proceedings of Rajasthan History Congress, 1976, pp. 26-36.

[13] The Bappabhattisuricharita and the Prabandhakosa place Lakshanavati, the capital of Dharma, on the banks of Godavari but in the Gauda desa.

[14] According to the Prabandhakosa, “by Yasodharman, the king of a neighbouring country.”

[15] According to some works Madrama hivijaya.

[16] It is interesting that the Nirmand copper plate inscription, which has been assigned by Fleet to the 7th century and by Cunningham to the 12th, a reference is made to Maharaja Samudrasena who ruled over Nirmand in the Kangra district (vide Fleet, Corpus, III, pp. 286).

[17] Or Khandya.

[18] S. R. Goyal, The Riddle of Ama-Nagavaloka of the Jain Tradition, Proceedings of Rajasthan History Congress, 1976, pp. 26-36.

[19] Gaudavaho, V. 69.

[20] Tripathi, R. S., History of Kanauj, pp. 212 ff.

[21] Ojha, G. H., E I. XIV. p. 179, n. 3; Majumdar, R. C., Journal of the Dept. of Letters, X, p. 45; Sharma, Dasaratha, Rajasthan through the Ages, p. 143.

[22] As recorded in the Jain Harivamsa.

[23] Sharma, D., op. cit., p. 143.

[24] Cf. Buddha Prakash, Aspects of Indian History and Civilization, pp, 113-16.

[25] Aiyangar, S.K., Ancient India and South Indian History and Culture, I, pp. 345 ff.; Choudhary, G.C. Political History of North India from Jain Sources, pp. 21 ff.

[26] Sinha, B.P., Decline of the Kingdom of Magadha, p. 368, n. 2.

[27] Vide The Classical Age, p. 131; Tripathi, loc. cit pp. 194 ff.

[28] Attention of scholars to this evidence has been drawn by Dr. P.K. Agrawala (The Quarterly Review of Historical Studies, Culcutta, XV, No. 2, pp. 109 ff.)

[29] Known from the Buchkala inscription (E I. IX, p. 198).

[30] It is inferred from the Barah plate of Bhojadeva (E I. XIX, pp. 15 ff.) which informs us of Nagabhata It’s approval of a grant in the Kalan- jaramandala of the Kanyakubjabbukti.

[31] E I. XVIII, pp 99 ff.

[32] According to R.C. Majumdar and Dasaratha Sharma this verse refers to the hill-forts of the kings of Apartta etc. But H.A. Phadake (All India Oriental Conference, Gauhati Session, Snmmaries of Papers, pp. 96-7) has shown that here reference is made to a place named Rajagiridurga which according to Alberuni was situated to the west of Lahore. We suggest that Samudrasena, whom Nagavaloka defeated at Rajagiridurga, may plausibly be identified with Samudrasena of the Nirmand copper plate inscription (Fleet, Corpus, III, pp. 286 ff).

[33] Aiyangar (loc. cit., p. 366) is wrong when he states that “the title Naga- valoka is given to his (Nagabhata II’s) grand-father in the Sagartal or Gwalior inscription of Bhoja”.

[34] E I, IX, p. 253; Tripathi, op. cit., p. 231.

[35] E I, II, p. 121, 126. See also I A, 1911, pp. 239-40 for the identification of Nagavaloka with Nagabhata II.

[36] Choudhary, loc. cit. p. 24.

[37] Ibid. p. 27.

[38] JDL, X. p. 46.

[39] E I, XIX, pp. 18, 19.

[40] Ibid. V, p. 213.

[41] Sharma, D., loc. cit., pp. 146 ff.